About

Kiran Ahluwalia is a modern exponent of the great vocal traditions of India and Pakistan which she honors intensely yet departs from in masterful, personal ways. Her original compositions embody the essence of Indian music while embracing influences from Mali and Western blues, rock, R & B and nuances of ...

Links

Contact

Current News

- 03/05/201805/04/2018

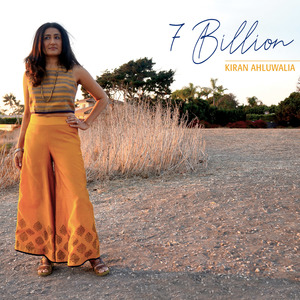

A Frequency of Her Own: Kiran Ahluwalia Synthesizes the Sonic World on 7 Billion

Kiran Ahluwalia had a small epiphany as she wrote what eventually became the title track for her latest album: The eruptions of intolerance and violence plaguing societies around the world had to be directly countered. Yet the focus on divisions and difference neglected a central fact, that we are all united in our difference and uniqueness. “There are seven billion of us now on Earth and every person has their own unique perspective and set of experiences,” she reflects....

- WorldMusic.org, 03/16/2018, WELCOME THE STRANGER featuring Kiran Ahluwalia, Souad Massi, Yasser Darwish, Bhai Kabal Singh at Berklee Performance Center Text

- NPR Northwest Public Broadcasting, Event preview, 03/12/2018, Kiran Ahluwalia Live at The Triple Door

- RootsWorld, Album review, 01/22/2018, Kiran Ahluwalia Text

- KMUW, Event preview, 03/12/2018, Women Of World Music, Ides Of March & Don Drummond (Skatalites)/Les Baxter Birthdays Text

- + Show More

News

Kiran Ahluwalia had a small epiphany as she wrote what eventually became the title track for her latest album: The eruptions of intolerance and violence plaguing societies around the world had to be directly countered. Yet the focus on divisions and difference neglected a central fact, that we are all united in our difference and uniqueness. “There are seven billion of us now on Earth and every person has their own unique perspective and set of experiences,” she reflects. “We each have our own way of dealing with things, of hearing things, of moving through life."

Ahluwalia, with over nearly two decades of music making that took her from Punjabi folk and Indian classical music to refreshingly original borderless songs, has found her own way on 7 Billion. (Six Degrees: May 4, 2018) Touching on the need for tolerance and boldness, the songs on 7 Billion encompass all Ahluwalia’s myriad musical fascinations: the guitar twang of Mali, the heavy heartbeat of Southern soul, the gorgeous nuance of Subcontinental sounds.

“I’ve taken aesthetics I love such as blues, Malian styles, and of course Indian forms and mashed them together in my own way,” explains Ahluwalia.

Ahluwalia will celebrate this album’s release with a spring US/Canadian tour, including several dates of her new live project LOVEfest, which bring spiritual performances from the Sikh and Sufi traditions together with contemporary sets by Algeria’s Souad Massi and Ahluwalia.

7 Billion pulls together songs that map out many of Ahluwalia’s interests and sonic loves. “Jhoomo (Sway)” was written to charm a shy lover in a steamy seduction scene in an as-yet unreleased film. “We Sinful Women” commissioned and composed for a dance company’s new work was based on a radical Pakistani feminist’s stirring poem. Yet most of Ahluwalia’s pieces are sparked by the diverse sounds she hears rolling around in her head. They often emerge in conversation with her life and musical partner, the highly acclaimed guitarist Rez Abbasi.

“I translate thought and emotion into sound in a very intuitive way,” says Ahluwalia. “I sometimes develop songs with Rez as we sit on the couch, either referencing tracks that are inspiring me or working on specific ideas that I've been living with. If we come up with something magical, I'll record it on my phone and listen to it later. That’s how songs often start.”

That’s not where they end. Ahluwalia will continue to refine and rethink the songs, adding layers of instruments. On 7 Billion, these layers built on Ahluwalia’s past explorations--Malian and desert blues, Portuguese fado, North American rock, Indian forms--for a sometimes raucous and raw sound that includes a soulful sweep of organ and glittering, growling guitars.

The music of “Khafa,” an impassioned call to set aside the religious strictures and orthodoxies that blind us to one another’s humanity, was inspired by West African styles. “I came up with the melodic idea and would hum it around the house. Rez said, ‘Hey, that sounds great.’ I had all these phrases all over the place, then I decided to develop it more to find meaning for the melody, which lent itself very well to talking about anger against the man made rules of religion.”

Ahluwalia brought similar intensity to “We Sinful Women,” rethinking it for the album. It was no easy feat to set the poem to music for a dance company’s performance, as its Urdu lines simply did not conform to usual song styles accompanying Urdu poetry. Ahluwalia did not let that faze her, and came up with a unique approach that resonated powerfully with audiences.

Yet after the dance piece premiered, the song stuck with her. She longed to hear it slightly differently: “I liked it but wanted to make it less polite and dainty, into a very militant and activist song, a strident battle cry,” she explains. “When I arranged it for the dance piece it had flute, sax, sarangi, and tabla. It was not traditional but softer in treatment. For my own record, I wanted to match the gritty activist nature of it in the arrangement and tonality. I asked Rez, and we spent a lot of time figuring out the heavy, gritty amp sound for the guitar.”

Grit also runs through “Kuch Aur (Something Else),” a bluesy examination of regret and sorrow that came to Ahluwalia after she got into Southern blues rock. A first for the songwriter, Ahluwalia came up with some English-language lyrics, only to translate them into Urdu because they just worked better that way.

The way Ahluwalia flows between seemingly farflung genres is no accident. It’s the natural progression of her exploration of what appeals to her; her refusal to see her Indian heritage as her defining characteristic. “I think of my music as creating a genre that’s on its own, one that benefits greatly from being in the diaspora,” she muses. “This isn’t the way Indian music is in any other part of the world. I hesitate to even call it Indian. We’re doing something that hasn’t been done before. It’s an organic hybrid that's reflective of so many personal and lived influences.” Ahluwalia is an artist and songwriter first and foremost, whose global ear catches frequencies that are hers alone.

Kiran Ahluwalia sat down one day and wrote a song, “Saat.” Its title, the number seven, reflected the seven billion quirky, distinct individuals on our shared planet. It tackled the nature of our widespread intolerance of one another. “The earth now holds seven billion people; for me this means there are seven billion unique ways of interpreting things,” she explains.

The song resonated. It was powerful. (It appears on her upcoming album.) But the two-time Juno-winning Indian-Canadian singer and composer wasn’t ready to stop there. “Having written the song, I still felt helpless about doing something about it. I wanted to bring about change, to reach out with the opposite of hatred,” says Ahluwalia. “I wanted to do more than sing about it. I wanted to bring music and dance from ‘outside’ in, and spark curiosity and connection.”

Ahluwalia invited elegant, arresting Algerian singer-songwriter Souad Massi to help her create a direct musical response to the ignorance and animosity many visible minorities and faith communities face. Contemporary voices that cross cultural and stylistic boundaries, Ahluwalia and Massi will play their original pieces and present their perspectives with songs that draw on and defy the traditions of their respective heritage.

The seeds of this shared concert grew from Ahluwalia’s own experiences as an Indian-born Canadian growing up in a complex cultural context. “As an immigrant child, the hardships we faced were touted as temporary, but the effects were permanent. On the one hand, I developed a wonderful double culture, two sets of wardrobe and multiple languages to think in. On the other, I developed conflicting etiquettes and ways of doing things that were neither ‘fully’ Indian nor ‘fully’ Canadian,” muses Ahluwalia.

Her struggles, she grasped, were not just her own: “Wherever we live, the majority’s way of doing things becomes the norm, and whatever is different and foreign can easily be mistrusted. The consequence in a large immigrant-based population in countries like Canada and the US can be cultural intolerance and difficulty in embracing newness.” Sometimes this suspicion erupts into full-blown violence and violation, as the rising numbers of hate crimes aimed at Sikhs and Muslims across North America post-9/11 demonstrate.

Ahluwalia longed to counteract this dynamic by presenting audiences with more familiar, but still fresh perspectives of two powerful women artists whose music touches on universal elements and themes. “Souad and I sing of the human condition, our personal stories as women and the stories of our communities in turmoil,” notes Ahluwalia. “This humanity runs through our work and is easy to hear, even if you are new to our musical backgrounds.”

Ahluwalia is accustomed to uniting seemingly disparate sounds and unexpected groups, an alchemist of cross-cultural collaboration. She created an entire album exploring how the bittersweet world of Portuguese fado can converse with Indian sounds, and she embraced the stark grooves of Saharan blues with friends Tinariwen, to dive into qawwali gems. Her work, like many of the poems and forms that inspire her, speaks simultaneously to earthly desires and lofty calls of the divine, the feel of R&B, rock and the nuance of jazz with the Punjabi folk and Indian classical music that formed the basis of her extensive vocal training. Massi, in her latest songs, has expanded her musical vocabulary by drawing on the sound and spirit of the American blues.

Ahluwalia longed to focus the love into one compelling evening. She had long admired Massi and, after months of attempting to track the singer down, finally heard that Massi had been following Ahluwalia’s work as well. “It just feels like our paths were meant to cross,” Massi says of the collaboration. “Through the power of music, pushing one to see beyond norms and prejudices, pushing the boundaries, I feel we are like sisters in music.”

Both artists are releasing new work this year, with Ahluwalia’s new album 7 Billion out May 4, 2018 on Six Degrees, a release honored by this US and Canadian tour. Massi has a yet-to-be-titled release due out in September 2018 (Believe/Naxos)

“The arts, and these artists in particular, are perfectly poised to create positive appreciation of Indian and Arab arts. It’s key that modern artists who have evolved with Western influence show that we’re all addressing the world and changing in our own individual ways,” says Ahluwalia. “That we are all one in seven billion, all strangers in need of welcome. That’s what this shared evening is all about.”

Kiran Ahluwalia sat down one day and wrote a song, “Saat.” Its title, the number seven, reflected the seven billion quirky, distinct individuals on our shared planet. It tackled the nature of our widespread intolerance of one another. “The earth now holds seven billion people; for me this means there are seven billion unique ways of interpreting things,” she explains.

The song resonated. It was powerful. (It appears on her upcoming album.) But the two-time Juno-winning Indian-Canadian singer and composer wasn’t ready to stop there. “Having written the song, I still felt helpless about doing something about it. I wanted to bring about change, to reach out with the opposite of hatred,” says Ahluwalia. “I wanted to do more than sing about it. I wanted to bring music and dance from ‘outside’ in, and spark curiosity and connection.”

Ahluwalia invited elegant, arresting Algerian singer-songwriter Souad Massi to help her create a direct musical response to the ignorance and animosity many visible minorities and faith communities face. Contemporary voices that cross cultural and stylistic boundaries, Ahluwalia and Massi will play their original pieces and present their perspectives with songs that draw on and defy the traditions of their respective heritage.

The seeds of this shared concert grew from Ahluwalia’s own experiences as an Indian-born Canadian growing up in a complex cultural context. “As an immigrant child, the hardships we faced were touted as temporary, but the effects were permanent. On the one hand, I developed a wonderful double culture, two sets of wardrobe and multiple languages to think in. On the other, I developed conflicting etiquettes and ways of doing things that were neither ‘fully’ Indian nor ‘fully’ Canadian,” muses Ahluwalia.

Her struggles, she grasped, were not just her own: “Wherever we live, the majority’s way of doing things becomes the norm, and whatever is different and foreign can easily be mistrusted. The consequence in a large immigrant-based population in countries like Canada and the US can be cultural intolerance and difficulty in embracing newness.” Sometimes this suspicion erupts into full-blown violence and violation, as the rising numbers of hate crimes aimed at Sikhs and Muslims across North America post-9/11 demonstrate.

Ahluwalia longed to counteract this dynamic by presenting audiences with more familiar, but still fresh perspectives of two powerful women artists whose music touches on universal elements and themes. “Souad and I sing of the human condition, our personal stories as women and the stories of our communities in turmoil,” notes Ahluwalia. “This humanity runs through our work and is easy to hear, even if you are new to our musical backgrounds.”

Ahluwalia is accustomed to uniting seemingly disparate sounds and unexpected groups, an alchemist of cross-cultural collaboration. She created an entire album exploring how the bittersweet world of Portuguese fado can converse with Indian sounds, and she embraced the stark grooves of Saharan blues with friends Tinariwen, to dive into qawwali gems. Her work, like many of the poems and forms that inspire her, speaks simultaneously to earthly desires and lofty calls of the divine, the feel of R&B, rock and the nuance of jazz with the Punjabi folk and Indian classical music that formed the basis of her extensive vocal training. Massi, in her latest songs, has expanded her musical vocabulary by drawing on the sound and spirit of the American blues.

Ahluwalia longed to focus the love into one compelling evening. She had long admired Massi and, after months of attempting to track the singer down, finally heard that Massi had been following Ahluwalia’s work as well. “It just feels like our paths were meant to cross,” Massi says of the collaboration. “Through the power of music, pushing one to see beyond norms and prejudices, pushing the boundaries, I feel we are like sisters in music.”

Both artists are releasing new work this year, with Ahluwalia’s new album 7 Billion out May 4, 2018 on Six Degrees, a release honored by this US and Canadian tour. Massi has a yet-to-be-titled release due out in September 2018 (Believe/Naxos)

“The arts, and these artists in particular, are perfectly poised to create positive appreciation of Indian and Arab arts. It’s key that modern artists who have evolved with Western influence show that we’re all addressing the world and changing in our own individual ways,” says Ahluwalia. “That we are all one in seven billion, all strangers in need of welcome. That’s what this shared evening is all about.”

Kiran Ahluwalia sat down one day and wrote a song, “Saat.” Its title, the number seven, reflected the seven billion quirky, distinct individuals on our shared planet. It tackled the nature of our widespread intolerance of one another. “The earth now holds seven billion people; for me this means there are seven billion unique ways of interpreting things,” she explains.

The song resonated. It was powerful. (It appears on her upcoming album.) But the two-time Juno-winning Indian-Canadian singer and composer wasn’t ready to stop there. “Having written the song, I still felt helpless about doing something about it. I wanted to bring about change, to reach out with the opposite of hatred,” says Ahluwalia. “I wanted to do more than sing about it. I wanted to bring music and dance from ‘outside’ in, and spark curiosity and connection.”

Ahluwalia created LOVEfest, a direct musical response to the ignorance and animosity many visible minorities and faith communities face. She brings together two performers closely tied to tradition and faith practice, both rarely enjoyed outside of their home communities, a Shabad Kirtan (Sikh Spirituals) ensemble (Bhai Kabal Singh Group, heard for the very first time on the concert stage) and an Egyptian dervish (Yasser Darwish, performing tanoura, a dance practice tied to Sufi ritual). To present other, more contemporary voices in broadening counterpoint, Ahluwalia performs her own music, originals based on Indian and Malian styles, and Western blues and rock, many from her new album Seven Billion (out May 4, 2018 on Six Degrees). She also invites elegant, arresting Algerian singer-songwriter Souad Massi to share her highly regarded perspective.

The seeds of LOVEfest grew from Ahluwalia’s own experiences as an Indian-born Canadian growing up in a complex cultural context. “As an immigrant child, the hardships we faced were touted as temporary, but the effects were permanent. On the one hand, I developed a wonderful double culture, two sets of wardrobe and multiple languages to think in. On the other, I developed conflicting etiquettes and ways of doing things that were neither ‘fully’ Indian nor ‘fully’ Canadian,” muses Ahluwalia.

Her struggles, she grasped, were not just her own: “Wherever we live, the majority’s way of doing things becomes the norm, and whatever is different and foreign can easily be mistrusted. The consequence in a large immigrant-based population in countries like Canada and the US can be cultural intolerance and difficulty in embracing newness.” Sometimes this suspicion erupts into full-blown violence and violation, as the rising numbers of hate crimes aimed at Sikhs and Muslims across North America post-9/11 demonstrate.

Newness bursts from the precisely timed swirling of Darwish’s vivid skirts, from the rich voices that usually only ring out inside the gurdwara (Sikh temple). It is framed by more familiar, but still fresh perspectives from two powerful women artists whose music acknowledges their heritage, yet departs from it in intriguing, relatable ways.

In the end, for all the external novelty of the performances, LOVEfest suggests that there are universal elements and themes that resound throughout these songs and movements. “Souad and I sing of the human condition, our personal stories as women and the stories of our communities in turmoil,” notes Ahluwalia. “This humanity runs through the work of all the other participants of LOVEfest as well.”

Ahluwalia is accustomed to uniting seemingly disparate sounds and unexpected groups, an alchemist of cross-cultural collaboration. She created an entire album exploring how the bittersweet world of Portuguese fado can converse with Indian sounds, and she embraced the stark grooves of Saharan blues with friends Tinariwen, to dive into qawwali gems. Her work, like many of the poems and forms that inspire her, speaks simultaneously to earthly desires and lofty calls of the divine, the feel of R&B, rock and the nuance of jazz with the Punjabi folk and Indian classical music that formed the basis of her extensive vocal training.

Ahluwalia longed to focus the love into one compelling evening, a tribute to the short but powerful festivals she often saw in India and places like the Apollo Theater, where several performers of different styles or regions would all share a stage for a night. “We think of festivals as long outdoor summer happenings,” says Ahluwalia. “But I have seen this kind of festival atmosphere concentrated in a single night. As an audience member, I loved that festival environment inside a theater. I had it in my mind that I wanted to do something like that one day.”

When the ideas came together as LOVEfest, Ahluwalia turned to performers she had a strong personal connection to. Strongest was to Bhai Kabal Singh, whose kirtan singing had moved her since she was a young girl attending Sikh services with her family. Ahluwalia longed to share this more broadly, as well as introduce North Americans to Islamic dance and movement traditions. She had long admired Massi and, after months of attempting to track the singer down, finally heard that Massi had been following Ahluwalia’s work as well.

“The arts, and these artists in particular, are perfectly poised to create positive appreciation of Sikh and Islamic arts. It’s key that the traditional performers are juxtaposed with more modern artists who have evolved with Western influence, to show that we’re all addressing the world and changing in our own individual ways,” says Ahluwalia. “That we are all one in seven billion, all strangers in need of welcome. That’s what LOVEfest is all about.”

Kiran Ahluwalia sat down one day and wrote a song, “Saat.” Its title, the number seven, reflected the seven billion quirky, distinct individuals on our shared planet. It tackled the nature of our widespread intolerance of one another. “The earth now holds seven billion people; for me this means there are seven billion unique ways of interpreting things,” she explains.

The song resonated. It was powerful. (It appears on her upcoming album.) But the two-time Juno-winning Indian-Canadian singer and composer wasn’t ready to stop there. “Having written the song, I still felt helpless about doing something about it. I wanted to bring about change, to reach out with the opposite of hatred,” says Ahluwalia. “I wanted to do more than sing about it. I wanted to bring music and dance from ‘outside’ in, and spark curiosity and connection.”

Ahluwalia created LOVEfest, a direct musical response to the ignorance and animosity many visible minorities and faith communities face. She brings together two performers closely tied to tradition and faith practice, both rarely enjoyed outside of their home communities, a Shabad Kirtan (Sikh Spirituals) ensemble (Bhai Kabal Singh Group, heard for the very first time on the concert stage) and an Egyptian dervish (Yasser Darwish, performing tanoura, a dance practice tied to Sufi ritual). To present other, more contemporary voices in broadening counterpoint, Ahluwalia performs her own music, originals based on Indian and Malian styles, and Western blues and rock, many from her new album Seven Billion (out May 4, 2018 on Six Degrees). She also invites elegant, arresting Algerian singer-songwriter Souad Massi to share her highly regarded perspective.

The seeds of LOVEfest grew from Ahluwalia’s own experiences as an Indian-born Canadian growing up in a complex cultural context. “As an immigrant child, the hardships we faced were touted as temporary, but the effects were permanent. On the one hand, I developed a wonderful double culture, two sets of wardrobe and multiple languages to think in. On the other, I developed conflicting etiquettes and ways of doing things that were neither ‘fully’ Indian nor ‘fully’ Canadian,” muses Ahluwalia.

Her struggles, she grasped, were not just her own: “Wherever we live, the majority’s way of doing things becomes the norm, and whatever is different and foreign can easily be mistrusted. The consequence in a large immigrant-based population in countries like Canada and the US can be cultural intolerance and difficulty in embracing newness.” Sometimes this suspicion erupts into full-blown violence and violation, as the rising numbers of hate crimes aimed at Sikhs and Muslims across North America post-9/11 demonstrate.

Newness bursts from the precisely timed swirling of Darwish’s vivid skirts, from the rich voices that usually only ring out inside the gurdwara (Sikh temple). It is framed by more familiar, but still fresh perspectives from two powerful women artists whose music acknowledges their heritage, yet departs from it in intriguing, relatable ways.

In the end, for all the external novelty of the performances, LOVEfest suggests that there are universal elements and themes that resound throughout these songs and movements. “Souad and I sing of the human condition, our personal stories as women and the stories of our communities in turmoil,” notes Ahluwalia. “This humanity runs through the work of all the other participants of LOVEfest as well.”

Ahluwalia is accustomed to uniting seemingly disparate sounds and unexpected groups, an alchemist of cross-cultural collaboration. She created an entire album exploring how the bittersweet world of Portuguese fado can converse with Indian sounds, and she embraced the stark grooves of Saharan blues with friends Tinariwen, to dive into qawwali gems. Her work, like many of the poems and forms that inspire her, speaks simultaneously to earthly desires and lofty calls of the divine, the feel of R&B, rock and the nuance of jazz with the Punjabi folk and Indian classical music that formed the basis of her extensive vocal training.

Ahluwalia longed to focus the love into one compelling evening, a tribute to the short but powerful festivals she often saw in India and places like the Apollo Theater, where several performers of different styles or regions would all share a stage for a night. “We think of festivals as long outdoor summer happenings,” says Ahluwalia. “But I have seen this kind of festival atmosphere concentrated in a single night. As an audience member, I loved that festival environment inside a theater. I had it in my mind that I wanted to do something like that one day.”

When the ideas came together as LOVEfest, Ahluwalia turned to performers she had a strong personal connection to. Strongest was to Bhai Kabal Singh, whose kirtan singing had moved her since she was a young girl attending Sikh services with her family. Ahluwalia longed to share this more broadly, as well as introduce North Americans to Islamic dance and movement traditions. She had long admired Massi and, after months of attempting to track the singer down, finally heard that Massi had been following Ahluwalia’s work as well.

“The arts, and these artists in particular, are perfectly poised to create positive appreciation of Sikh and Islamic arts. It’s key that the traditional performers are juxtaposed with more modern artists who have evolved with Western influence, to show that we’re all addressing the world and changing in our own individual ways,” says Ahluwalia. “That we are all one in seven billion, all strangers in need of welcome. That’s what LOVEfest is all about.”